Monitoring REDD+ Safeguards with Communities in Mai Ndombe District

By Cyrus Sinai, Benoit Thuaire, Serge Bondo and Leo Bottrill

Lake Mai Ndombe, site of the ERA project.

Moabi’s safeguard monitoring approach

A REDD+ Safeguard Information System (SIS) requires not only rigorous data collection on local social/environmental investments and grievances but must also adapt to the constraints of regions with limited infrastructure and financial resources . In collaboration with OGF, OSFAC, and local communities, Moabi has piloted a safeguard monitoring system in the ERA project [1] implemented by Wildlife Works Carbon in the Mai-Ndombe district of DRC. This novel monitoring system uses GeoODK – a free and open-source smartphone application – to collect and transmit crucial data on deforestation and the status of social/environmental safeguards in the project zone (such as to the development of new health centers and schools) to the Moabi online platform. This information is then shared with Congolese government authorities, REDD+ project partners, and independent observer organizations. This monitoring mechanism communicates in a chain between community observers at the village level, an intermediary focal point based in Inongo (Mai-Ndombe district’s administrative center), and the REDD mandated observers based in Kinshasa.

Why do we need community monitoring networks?

Due to Mai Ndombe’s size and remoteness, REDD+ social/environmental safeguards and grievances have not been effectively monitored. Drawing lessons from IM-FLEG, independent monitoring is infrequent – typically for 3 days once every 2-3 years – as well as expensive, requiring teams to be flown from Kinshasa over 400 kilometers away. Official audits conducted by bodies certified by the VCS and CCBA have typically involved only 1 week field visits every 3 years. In addition, non-mandated monitoring of REDD+ safeguards and grievances has generally been conducted on an ad hoc basis by advocacy-oriented NGOs. While data collection had provided useful information, it was not impartial and did not have access to comprehensive documentation of activities or maps from the REDD+ project proponents.

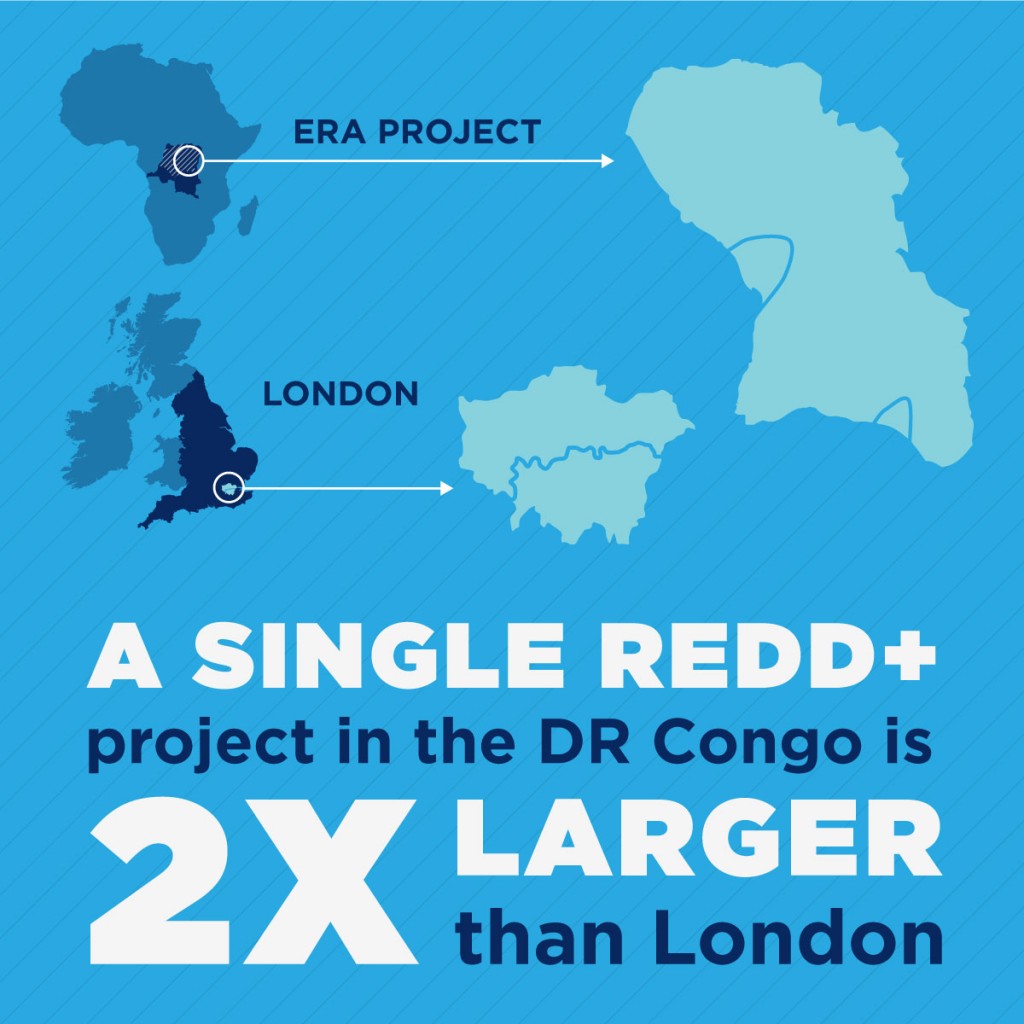

ERA project zone compared to London

How does a community monitoring network work?

To frequently transmit comprehensive and impartial data requires a low-cost mandated monitoring methodology and technology, which operates between non-mandated and project proponent systems. Moabi’s pilot community monitoring system was informed by OGF’s scoping missions to the ERA project, which provided valuable baseline data on REDD+ activities in the region and local communities’ concerns over social/environmental initiatives. Villages from which community observers selected had to fit four criteria; 1) accessible by transport, 2) have more than 50 inhabitants, 3) have had past or present REDD+ project activities, and 4) be spatially representative of the project zone, reflecting the area’s ethnic and environmental diversity.

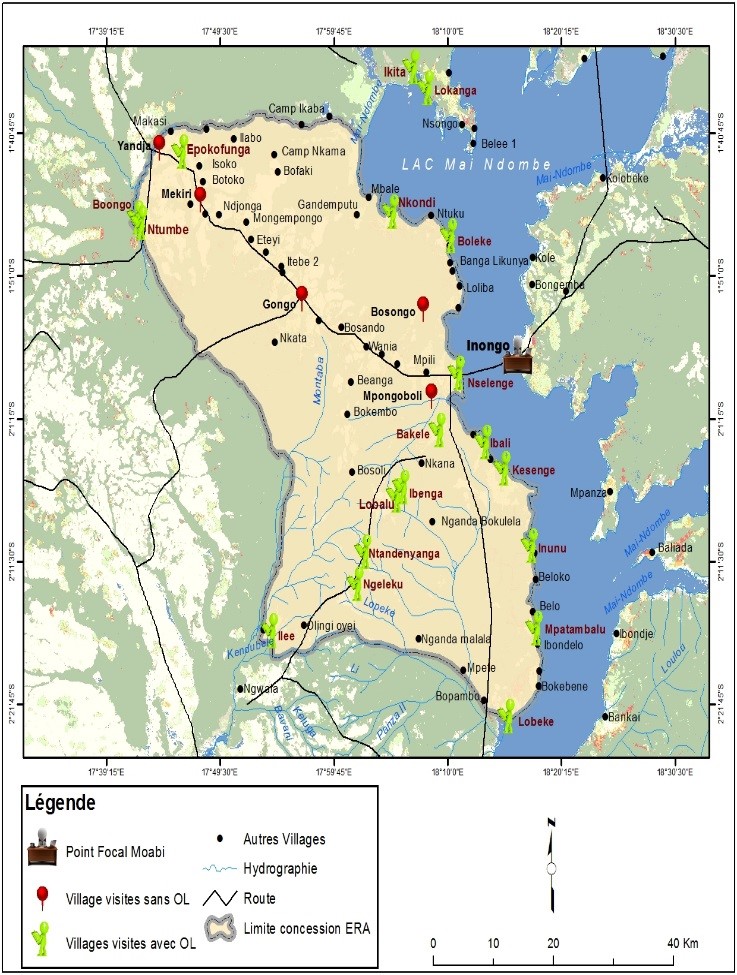

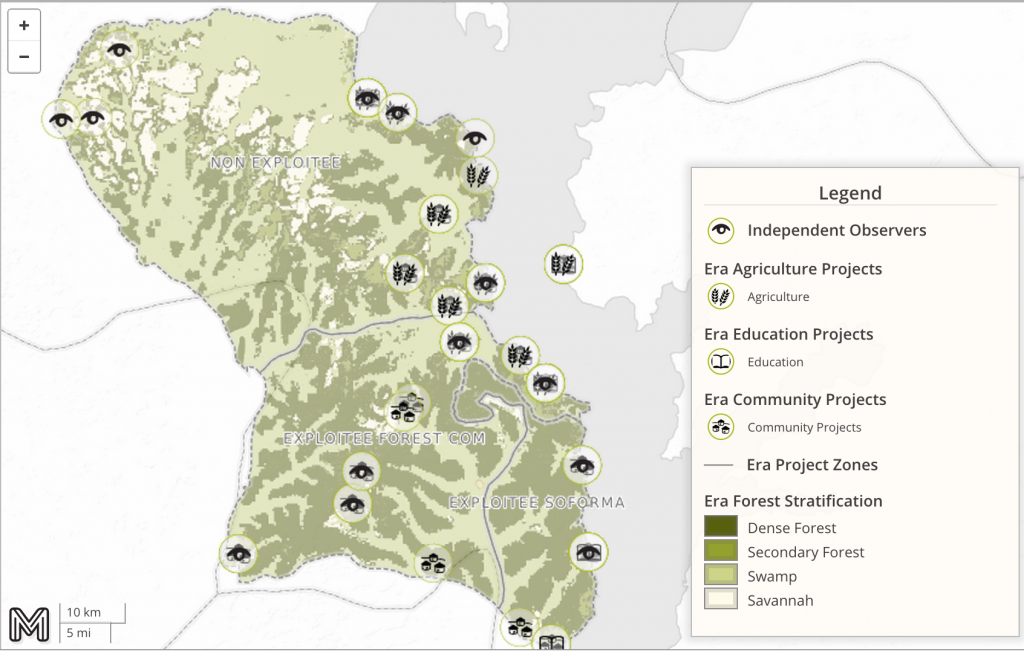

ERA project zone with locations of community observers and focal point.

Consent and transparency were key to the recruitment process. After meeting with district authorities in Inongo, Moabi team members consulted with local village chiefs to discuss the the pilot monitoring approach. Community meetings were held in villages to introduce the REDD+ monitoring process, discuss its potential benefits, and to obtain consent to participate. Community observers were ultimately selected by both the village chief and by community consensus, and were community members known to be honest and capable by their peers, representing the village’s best interests, and having no direct ties with either the REDD+ project or the Congolese government.

Liongo Alain, a community observer at Ngeleluku village.

John Mboloko, the project focal point based in Inongo.

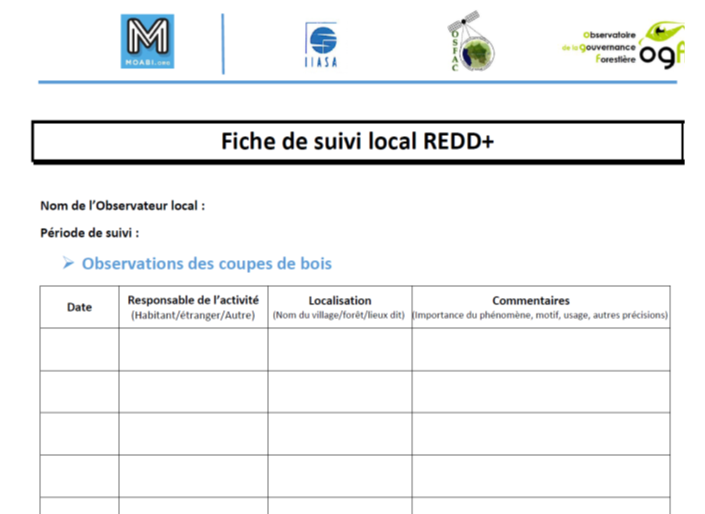

The recruited community observers were then trained during workshops on how to record observations of deforestation and safeguard infractions on easy-to-use report sheets. These sheets allowed for community observers to record quantifiable information on the status of safeguard projects so that they could be held accountable, such as whether a community agriculture project had created employment and produced expected yields, or whether a schoolhouse construction was progressing as planned. The forms also provided an avenue for reporting complaints such as the land tenure conflicts, lack of consultation, or benefit sharing disputes. Community observers are not paid directly for their time; however, they do receive compensation from the project in the form of petrol, rice, cooking oil, or other household consumables.

Benoit Thuaire and Serge Bondo of Moabi train community observers on how to record observations during a workshop.

To facilitate data collection from the community observers in the ERA project zone, Moabi recruited a focal point based in Inongo. Throughout the pilot period, the focal point went “on mission” every month for up to two weeks at a time, during which he visited community observers in their respective villages to collect data. Due to the vastness of the region and time constraints, the focal point would alternate every month between two circuits of villages; thus, every community observer was visited on a bimonthly basis. During these meetings, the focal point collected the observation sheets and examined the consistency of the recorded information through discussions with community members, aided when necessary, by a local translator. These meetings could take anywhere from 30 minutes to a several hours, in which case the local observer would bring him to the safeguard infraction location to take photographs and GPS coordinates.

Example of an observation sheet used by community observers.

Instance of deforestation recorded by community observer in Lokanga village.

All information gathered during the meeting was recorded by the focal point on the GeoODK application on a ruggedized smartphone [2] provided by Moabi. Upon returning to Inongo at the end of each mission, the focal point transmitted this data via the internet to Kinshasa for further validation and discussion with the mandated monitors. This data is then processed and made publicly available on Moabi’s online mapping platform, where additional Moabi map layers (such as REDD+ project boundaries, forest cover data, and regional infrastructure) can be added to provide additional context to the monitoring project.

What are the results?

During the pilot phase, Moabi monitoring system has provided an extensive georeferenced database of social and environmental programs in the ERA project zone, as well as instances of deforestation. This data has been accompanied by documentation of community grievances and concerns with project initiatives. The information collected is being used in the project’s first monitoring report, which is to be published in August 2015. Moabi’s monitoring system provides a dynamic interface where social safeguards and instances of deforestation are able to be observed in a meaningful timeframe by both stakeholders and by the public online.

ERA environment types and social safeguard projects mapped on the Moabi online platform.

Benefits and Limitations

Moabi’s pilot monitoring system has thus far demonstrated several advantages over previous monitoring methods, as well as limitations. The use of a focal point based locally in Inongo reduces the need for mandated monitors to make costly missions from distant Kinshasa. The data collection/transmission system is low-tech, making it both affordable and replicable for future projects on a wide spectrum of possible land use activities. The engagement of community members and traditional leaders also empowers local communities to have a greater sense of ownership and involvement in the safeguard monitoring process. The information obtained has also provided an extensive and valuable database that can be used for future project audits and by other third party organizations working in the region. The database will be helpful to both project proponents, project auditors, as well as non-mandated monitoring organizations.

Transmission of collected data to Moabi’s online platform is not real time and carries a lag period of several days to even weeks. However, this was seen as more sustainable than mass-distributing expensive mobile technology to remote communities unaccustomed to such devices. Past experience suggest this often leads to breakages and the potential loss of data. The data gained during the pilot study was also limited because OGF and Moabi were operating without an official government mandate. This made data collection from Wildlife Works more time-consuming and bureaucratic.

Although the safeguard monitoring method demonstrated by Moabi and OGF have advantages over existing methods, this process still needs to be complemented by a GRM (grievance redress mechanism) system that can operate at both the jurisdictional and national levels. However, there are many gaps in the legal system related to REDD+. Whether these gaps are about the implementation of the FPIC, the management of potential leaks, the inclusion of HCV forests, concepts of permanence and additionality, as well as participation, profit-sharing and complaint resolution mechanisms, it is undeniable that currently a clear and robust legal framework is required to endorse REDD + projects and initiatives in the DRC. The two major initiatives, including the signing of the Decree No. 004 / CAB / MIN / ECN-T / 012 of 15 February 2012 and its procedure manual, would be significant steps toward addressing these gaps in a current revision process. Without improving legislation in the sector and taking into account the identified loopholes, it will be difficult for any organization to operate as a mandated observer and ensure that safeguards are being implemented.

Next Steps

While the lack of legal framework related to REDD+ remains an impediment, Moabi will continue to develop methodologies and monitor existing REDD+ projects. An IM-REDD methodology, legality grid, and our first monitoring report from the ERA project will be released in August. To support development of a national REDD+ strategy, Moabi is working in partnership with CODELT and WRI to develop an official certification, gender strategy, and a grievance procedure manual. Furthermore, Moabi has signed a data sharing agreement with WWF-DRC and has begun making their REDD+ project data from Mai Ndombe available through the Moabi online platform. Moabi is continuing to work with its partners to refine and improve the monitoring of REDD+ projects, with collaboration and insights from other environmental organizations testing similar systems and technologies.

[1] The name ‘ERA’ was initially named after the initial project proponents ERA Ecosystem Services. In 2012, The project was bought outright by Wildlife Works Carbon though the project is still called ERA.

[2] Samsung Galaxy Xcover GT-S5690